What Is Fine Art Photography: Secrets Of Unique Visuals

October 31, 2025

Wondering what is considered fine art photography? Look for a clear idea, not just a pretty picture.

Fine art photography is not a trick. It is a decision. It begins when the camera becomes a way to show an idea instead of just recording a scene. What matters is that every element in the frame feels chosen, not accidental. This article walks you through what I look for when selecting a subject, how I shape light and texture, and the practical moves photographers use to turn small moments into necessary images.

Fine Art Photography Defined

When someone asks to define fine art photography, they want the border between craft and art. I think of it as photography where the primary intent is expressive. The image exists first to communicate a concept or emotion rather than only to document a product or event. If you want concrete examples, picture a single chair on a foggy shoreline, a still life of browned leaves lit by a single window, or a portrait where the subject’s hands tell a story. The face is almost secondary.

When someone asks to define fine art photography, they want the border between craft and art. I think of it as photography where the primary intent is expressive. The image exists first to communicate a concept or emotion rather than only to document a product or event. If you want concrete examples, picture a single chair on a foggy shoreline, a still life of browned leaves lit by a single window, or a portrait where the subject’s hands tell a story. The face is almost secondary.

How Fine Art Differs from Commercial and Documentary Photography

The difference shows in the choices made before and after the shutter clicks. Commercial work answers a brief. Documentary work answers the truth. Fine art answers curiosity and a question. To clarify what type of art is photography, treat photography as a visual language. It sits among conceptual art and visual storytelling. A commercial still life might be about selling shoes. A fine art still life is about absence, perhaps loss, made through objects and light.

The difference shows in the choices made before and after the shutter clicks. Commercial work answers a brief. Documentary work answers the truth. Fine art answers curiosity and a question. To clarify what type of art is photography, treat photography as a visual language. It sits among conceptual art and visual storytelling. A commercial still life might be about selling shoes. A fine art still life is about absence, perhaps loss, made through objects and light.

Another difference is reproducibility and editing. Fine art photography is often produced in limited editions, printed carefully, and framed as an object. Today, even how we share such work matters. Many artists look for an alternative to Instagram for artists to present their portfolios in a space focused on art, not algorithms. That intent changes how the photographer composes and finishes an image. When asked what is a fine art photographer, answer is: someone who frames personal ideas as photographs meant for contemplation and display.

Core Elements That Shape Fine Art Visuals

These are the deliberate choices that elevate a picture from pretty to necessary. Below, I break down the elements I return to repeatedly when I want an image to feel intentional and alive.

Concept and Emotion Drive the Image

At the heart of fine art is a central idea. Ask yourself what the image will be “about” in one line. A concept could be memory, waiting, abandonment, or domestic ritual. Once the concept exists, every choice must serve it. Consider a project about memory where I photographed old jackets arranged on chairs under attic light. The jackets are not the subject. The absence of the bodies is. That is an example of what makes a photograph fine art: alignment between the idea and every visible decision.

Practical checklist for concept-led shooting:

Write a one-sentence concept before the shoot.

Choose one dominant emotion and three supporting visual elements.

Remove anything that competes with the idea.

Composition, Lighting, and Texture Decisions

Composition is not only about rules. It is a set of choices that prioritize meaning. I prefer compositions that allow space for the viewer to land and then wander. That is why negative space often appears in fine art; it’s part of what makes fine art photography feel intentional rather than accidental.

Lighting choices are equally intentional. Soft northern light gives quiet, reflective images. High side light creates texture and age. Texture itself, wall plaster, linen, and skin become vocabulary words, and they are used deliberately.

A simple composition:

Primary subject placement: center or off-center by intent.

Secondary elements: do they support or distract?

Light quality: soft, hard, rim, or flat, and why.

Post-Processing’s Role in Fine Art

Post-processing is not a fix. It is a second act. Cropping, contrast control, and subtle dodging and burning are where you finalize the mood. I sometimes create a short action list: lift shadows, clamp highlights, and apply a low-contrast matte curve. For batch tasks that preserve consistency across prints, I use an AI batch photo editor to keep color and tone coherent across a series.

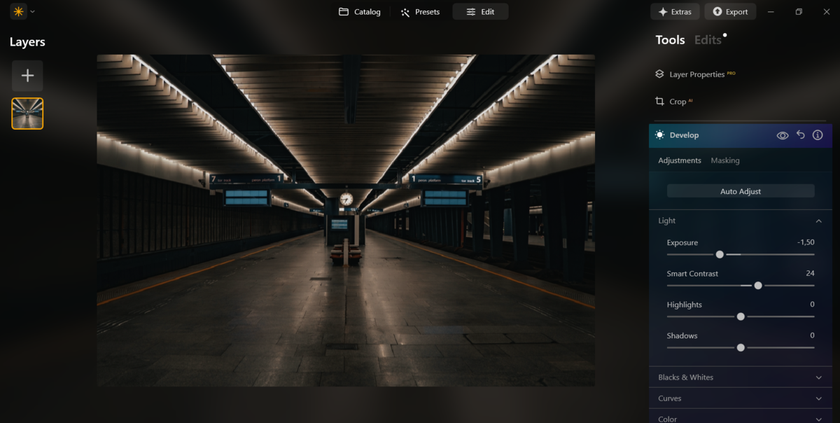

For example, I converted RAW files to muted tones for a series about empty train stations, reduced midtone contrast, and kept skin tones slightly warm. The result was a steady mood across six prints, which made the series feel like a single voice rather than six separate images.

Transform Your Photos into Classic Monochrome

Try it in Luminar NeoCultivating Your Fine Art Signature

Developing a signature starts with tiny, repeatable decisions, such as the way you light a subject, the color palette you favor, and the negative space you leave. Those small habits add up until viewers can recognize your work before they read your name. Understanding the fine art photography meaning helps you understand that your style isn’t just visual; it’s how you communicate emotion and intent through every frame.

Finding Inspiration and Personal Themes

Find the subjects you keep returning to. These themes become your fingerprints. I have returned to doorways and chairs for years because they let me ask questions about arrival and absence in different small towns. To discover yours, try this exercise: photograph one subject for a week using only one lens and one light source. The patterns that repeat point to your themes.

Use this prompt list to find themes:

Places that make you pause.

Objects you notice in other people’s homes.

Emotions you photograph without naming.

Using Color, Light, and Mood Consistently

Consistency is a signature. Decide on a color palette and a light recipe, then stick to it across a series. For a moody project, I lean heavily on cool blue shadows and small warm highlights. For brighter projects, I choose desaturated pastels and broad soft light.

When you need a quick, accurate conversion to black and white to test composition, try the simple step to change image to grayscale. Converting early lets you see whether the image reads without color. Real work with tone often reveals composition problems faster than color does.

Turning Ordinary Scenes into Artistic Statements

Turning the ordinary into art requires a brief: what statement do you want that scene to make? A grocery aisle can become a portrait of consumer behavior; a puddle on a sidewalk can become a low mirror of a city’s geometry.

The trick is narrowing choices and applying a few fine art photography techniques that guide how you frame and simplify. Limit props. Limit angles. Ask: What will the viewer notice first, and what will they notice last?

I keep a small list to test ordinary scenes:

Remove one element and reshoot.

Shoot from two heights: eye level and low.

Shift the light by 30 degrees and compare.

Techniques and Tools Used by Fine Art Photographers

Techniques and tools shape how your idea reads on the frame, so choose methods that deepen the mood rather than distract from it. Some of the most useful fine art photography tips I’ve learned come from slowing down, noticing small differences in light, and letting the image breathe before you press the shutter.

Camera Settings for Intentional Expression

Technical choices must be expressive. A wide aperture isolates the subject and collapses space. A narrow aperture holds detail across a scene for contemplative images. If you want texture in the foreground and background, choose f/11. If you want a single object to float, choose f/1.8 to f/2.8.

For instance, I shot a portrait of a potter at f/1.8 to blur the wheel behind the hands. The blur became a gesture, not noise. That small technical move made the hands read as the main subject, one of my favorite fine art photography examples of how camera settings can turn a simple portrait into an expressive statement.

That small technical move made the hands read as the main subject, one of my favorite fine art photography examples of how camera settings can turn a simple portrait into an expressive statement.

Using Minimalism and Negative Space Creatively

Minimalism is not emptiness. It is a deliberate shape and silence. Negative space defines the subject. Consider one photograph I made of a single coat hook with a single scarf. The emptiness around the hook told more than any cluttered room could. Minimalism forces clarity of idea.

The emptiness around the hook told more than any cluttered room could. Minimalism forces clarity of idea.

Try this negative space practice:

Frame so 60 percent of the image is empty.

Place the subject on the inner third, not the outer.

Remove color from the empty area to focus the eye.

Experimenting with Long Exposure and Motion Blur

Long exposure gives time to the image. Motion blur can suggest memory and movement without showing the subject clearly. I once photographed a ferryman pushing a boat with a 1.6-second exposure. The water smeared into a ribbon and the ferryman’s silhouette anchored the image. The blur read as weather and passage rather than technical trick.

For portraits that still need focus on the face, try selective motion in the background. For painted bokeh effects in portraits, use tools like portrait bokeh AI to explore how a softer background changes the image’s mood. Use it experimentally and then refine with in-camera moves.

Wrapping It Up

Fine art photography is a discipline of choices. It starts with a clear idea and continues through composition, light, and finish. If you want to know how to create fine art photography, start by naming your concept, limiting your tools, and shooting one theme until the images converge. Real projects reveal strengths and weaknesses quickly. Along the way, learn fine art photography strategies, practice small experiments, and keep a short checklist that reminds you why you made each picture.